Do you have mining ancestors? Get ready for a compelling dig (pun intended)!

Nearly every family oral history contains a story about how the family is related to some rich and famous person, perhaps even to royalty. And while many people can trace their family line back to Kings and Queens, the truth is that most of us will be researching for a VERY VERY long time before we can actually prove our connection to these individuals, if at all. The fact for many Americans is that we likely descend from more “salt of the earth” kind of people. And if your ancestors happened to be salt miners, I mean that quite literally. My point is that historical records show that many of our family trees include those who earned their living in the mining occupation.

In my own family tree, my 2nd great-grandfather worked, and perhaps even died, in the sulfur mines of Sicily’s Agrigento hills. Another second great-grandfather, born in East Prussia, migrated to the coal regions of Westphalia, where he worked as a miner before immigrating along with his wife and children to the coal regions of central Illinois. The family did not stay long in central Illinois. My ancestor eventually left the mining occupation when the family moved on to Chicago. Sadly, he passed away of pneumonia at the age of fifty.[1] I have often wondered if his many years in the coal mines made his lungs less able to withstand the dangers of that illness.

I recently finished a client report for an individual who, like me and many others, possesses a family history of coal mining. In this research project we learned that her family’s mining history included work in regions of New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Wales, and England. The family migrated west almost certainly in pursuit of better-paying mining work.[2] This client project in fact largely inspired this post, because here’s the thing: Although we may find it interesting to think that our family may have descended from royalty, from a genealogical perspective, mining ancestry can also provide an exciting and interesting research opportunity. Here’s why:

1. The mining occupation was (and is) often a hazardous one.

Especially historically, miners faced significant risks each day to earn a living. An understanding of the work environment, long hours and often meager pay naturally will inspire a sense of awe and appreciation for what our ancestors endured to earn a living.[3] Pride too naturally arises, as evidenced by the great number of associations and historical societies that have been created to preserve the memory of bygone mining communities around the world.[4]

In terms of genealogical value, the mining occupation often means voluminous records. When accidents happened, those were documented. Newspapers wrote about them. When labor disputes arose, those were documented and written about. So even if you think your ancestors were not “important enough” to be named in many records, you may be surprised once you start digging.

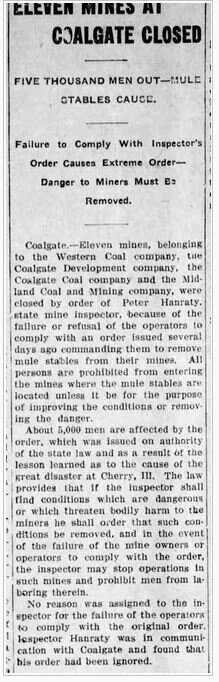

For example, my client’s ancestors were involved in several mining accidents. Online sources alone revealed quite a few records of accidents. And likely many more records exist elsewhere that have yet to be digitized. Other ancestors of my client worked for mines which were considered among the most dangerous in the US at that time. One such mine was reportedly forced to close due to failed safety inspections. Historic newspapers revealed details about some these accidents and working conditions:[5]

Newspapers represent only one source of mining accident records. You may also find a record of your ancestors’ involvement in official inspection reports. For US mining accidents, consider searching the Ancestry database titled, “U.S., Mining Accidents, 1839-2006.” If you ancestor’s name appears in this database, use the information provided to find the original record elsewhere.

For example, my client’s ancestor, Walter Pope, appeared in the Ancestry database:[6]

I used additional sources to prove his was the correct Walter Pope and not another individual of the same name.[7] Then, I used the information provided to find the original record giving details of the mining accident in which Pope was involved. According to the official report by the Pennsylvania Inspector of Mines, Pope was “Severely crushed by a fall of coal.”[8]

2. The mining occupation for our ancestors often began during childhood.

Child labor laws are a relatively modern social development. Historically, in mining communities, many children would have begun work from a young age. Although the children’s tasks would have been less labor-intensive than those of their adult counterparts, the tasks children performed still often came with significant risk. The children would also have worked tragically long hours.[9]

Though historically, many post-industrial revolution industries exploited children, the mining occupation specifically drew the attention of reformers in the early part of the 20th century. For an eye-opening read, check out this short article and accompanying photos: “The Photos That Helped End Child Labor in the United States.”[10]

Census records, the backbone of many genealogy research projects, will often reveal if you have mining ancestors in your family tree, and specifically, if your ancestors worked in the mines from a young age. For example, this 1851 Census of Wales record shows that nine-year-old Walter Pope worked as a “coal miner.”[11]

3. The mining occupation created mining communities with unique identities and histories.

In the United States, new mines often sprang up in remote regions. Partly due to the mine locations in remote areas, the mining companies would often provide to their employees homes, medical care, as well as a place to shop in the form of the “company store.” These remote mining communities became known as “coal camps” or “patch towns.” However, the provisions supplied by the coal company to their employees mostly benefited the coal company itself by keeping employees in the company’s debt. Rent and medical costs would have been subtracted from the employee’s pay, with any remaining earnings paid to the employee in the form of “scrip.” The mining employees could then use the scrip to make purchases on significantly marked-up goods at the company store. Only when the coal camp grew to the size to attract independent commerce could miners begin to earn any independence from the coal company.[12]

Family history researchers may be interested to know that mining community memorabilia, such a company store scrip or post cards can still be found for sale on Ebay. How cool would that be to find scrip from the company store where your mining ancestor shopped?

Do you have ancestors who worked as miners in the United States or elsewhere? Chances are good that you might. As always, the best place to start is with what you know. Use home sources first and then delve into the records to find what you might discover. And if you are able to find record of your family and secure a piece of historic mining memorabilia, well, I would love to see what you found. Shoot me an email at historyrunner17@gmail.com!

[1] Personal files of author, Laura Scalzitti (historyrunner17@gmail.com).

[2] Client research report prepared by author, Laura Scalzitti (historyrunner17@gmail.com) [title of report is intentionally omitted for privacy], January 2021.

[3] Peggy Clemens Lauritzen, “Dark as a Dungeon: Researching Mining Records,” Legacy Family Tree Webinars (familytreewebinars.com : accessed 17 January 2021).

[4] Personal Knowledge of author, Laura Scalzitti (historyrunner17@gmail.com). Scalzitti has researched a number of historic mining localities both personally and professionally, and has found many such societies exist in various places around the world.

[5] “Eleven Mines at Coalgate Closed,” The Foraker Tribune (Foraker, Oklahoma), 24 December 1909, p.2; digital image, Newspapers (Newspaper.com : accessed 16 January 2021).

“Accident in the Mines,” Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), 12 December 1874, p.4; digital image, Newspapers (Newspaper.com : accessed 23 January 2021). For photo see Lykens & Wiconisco Historical Society, Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/landwhistorical/photos/1906469542901616 :accessed 20 January 2021), digital image, unknown date, added 10 May 2017.

“County Items,” The Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), 17 September 1881; digital image, Newspapers (Newspapers.com : accessed 23 January 2021).

“Anthony Shaw killed at No. Five Mine,” The Coalgate Courier (Coalgate Oklahoma), 9 December 1917, p. 1; digital image, Newspapers (Newspaper.com : accessed 16 January 2021).

[6] “U.S., Mining Accidents, 1839-2006,” database online, Ancestry (Ancestry.com : accessed 15 May 2021), search for Walter Pope, accident at Short Mountain, Pennsylvania, 12 December 1874.

[7] Client research report prepared by author, Laura Scalzitti (historyrunner17@gmail.com) [title of report is intentionally omitted for privacy], January 2021.

[8] Pennsylvania Inspectors of Mines, Reports of the Inspectors of Mines of the anthracite coal regions of Pennsylvania for the year 1874 (Harrisburg: B.F. Meyers),1875, p. 28: digital image, Internet Archive (archive.org : accessed 20 January 2021).

[9] Peggy Clemens Lauritzen, “Dark as a Dungeon: Researching Mining Records,” Legacy Family Tree Webinars (familytreewebinars.com : accessed 17 January 2021), Introduction & Mule Driver.

[10] Mark Murrmann, “The Photos that Helped End Child Labor in the United States” Mother Jones, 3 October 2015, Mother Jones (https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2015/10/kids-coal-mines-lewis-hines-photos/ :accessed 25 January 2021).

[11] 1851 Wales Census, County Monmouthshire, Aberysruth, p. 9, entry 27, John Pope Family, Walter Pope; digital image, Ancestry (Ancestry.com : accessed 15 May 2021), Monmouthshire > Aberystruth > ALL > district 4 > image 10 of 30; citing National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surry, Class: HO107; Piece: 2447; Folio: 319; Page: 9; GSU roll: 104184.

[12] Eric Goostree, “Mining Towns,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=MI042 : accessed 16 January 2021.) Also, Peggy Clemens Lauritzen, “Dark as a Dungeon: Researching Mining Records,” Legacy Family Tree Webinars (familytreewebinars.com : accessed 17 January 2021). Also, Anthony F.C. Wallace and Paul A.W. Wallace, “Living Conditions-Life in the Patches,” The Old Country in the New World (https://amphilsoc.org/exhibits/wallace/patches.htm : accessed 21 January 2021). 68 Anthony F.C. Wallace and Paul A.W. Wallace, “Living Conditions-Life in the Patches,” The Old Country in the New World (https://amphilsoc.org/exhibits/wallace/patches.htm : accessed 21 January 2021).

[13] For photograph see, "Coal Mine Coalgate Oklahoma - Rare Postcard dated 1912; Antique Mining Postcard OK County Railroad 1912," item no. 323984301639, Ebay (Ebay.com : accessed 18 January 2021), digital image, posted by pstcardman2014.

[14] “Coal Scrip Token🔥25c Lynn Camp Coal Company Gray,KY ⛏️Knox County,” item no. 124720368160, Ebay (Ebay.com : accessed 15 May 2021), digital image, posted by

bigredscards.